Where Does the Time Go?

In a previous post, Engineering Leaderships Biggest Challenge, I highlighted the frustrations that can exist between business stakeholders and engineering teams, especially regarding the perception that features are taking too long to deliver. In today’s fast-paced business environment, stakeholders often hope that new ideas or customer requests can be implemented in days rather than weeks, or weeks rather than months. Under such time pressure, they often look at the engineering group—typically one of the largest teams in the organization—and wonder, “Where does the time go?”. This question is usually asked with feature delivery in mind.

Engineering teams juggle multiple responsibilities. We build product features, address quality issues, safeguard systems and data against cybersecurity threats, and manage technical debt to maintain or improve delivery speed as systems grow in complexity. However, stakeholder engagement tends to focus on product features and updates, while other tasks are seen as internal engineering responsibilities. Although there’s some truth to this, it presents a significant problem for engineering.

When interactions and reporting focus solely on product features, it’s natural to assume that most of engineering’s time and capacity is also dedicated to these tasks. While stakeholders might have a vague understanding that other work is happening, it’s often perceived as operational, mundane, and routine. Yet every task in engineering has a cost associated with it. Each item requires a commitment of people and time. Because work can’t be done for free, it’s critical to understand delivery investment. That is, how do we balance different types of work and how much time and effort do we commit to each. Let’s look at a real-world example that uses flow data to reveal hidden inefficiencies and poor investment practices within an organisation.

Delivery Investment by Example

In a recent engagement with a successful and growing mid-sized organisation, we analysed delivery data over a five-week period to assess the performance of their delivery system. As usual, our goal was to create visibility using flow metrics to highlight inefficiencies and identify areas for improvement. Prior to gathering the data, we encouraged the organisation to assign all work into one of four different categories:

- Story: All product feature work,

- Bugs: All defects,

- Risks: All security, compliance and governance work and,

- Debt: All technical debt work.

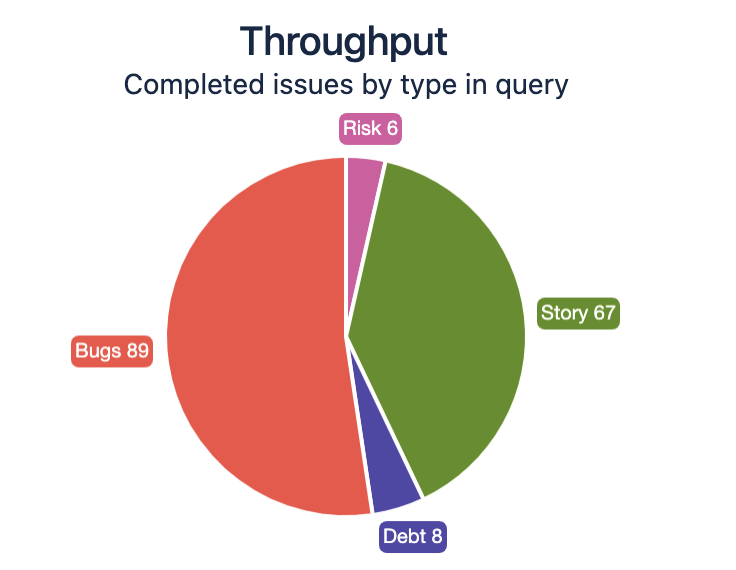

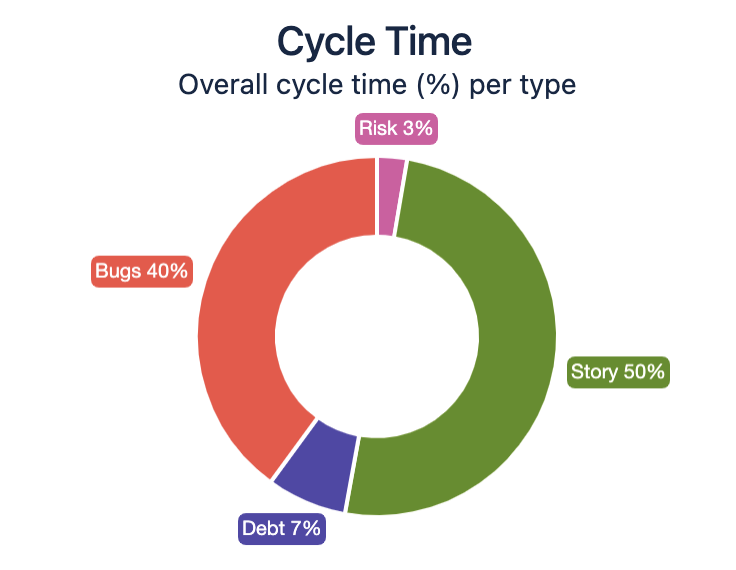

What we discovered was certainly interesting and challenged existing perceptions within the organisation. The data in figure 1 shows that out of 170 items delivered over five weeks, 89 were bug fixes. That is 52% of total deliveries. These fixes consumed 40% of the total cycle time. This significant investment in quality had largely gone unnoticed before this data became available.

Figure 1. Throughput and Cycle Time Delivery Investment from Delivery flow

Interestingly, the business didn’t perceive there to be a quality problem as customers rarely reported production issues. However, upon closer examination, we discovered that most of the reported issues were caught internally by the QA team during the development process. While the unintentional creation of bugs is inevitable in software development, the team was doing such a good job of catching and fixing these issues before they hit production that the extent of investment in this area was not visible or understood.

The organisation’s success and growth created a sense that “How we are working is working well”. From a production quality perspective, this team was doing a good job but it was doing it inefficiently. Investing 40% or more of your time in quality issues can sometimes be necessary, but this investment wasn’t intentional—it was a side-effect of flaws in the team’s development process that had not been visible before. The team was uncomfortable with the data, but after taking the time to understand the source of these defects, they saw an opportunity for improvement. They’re now executing a plan to reduce the 40% cycle time to 30% within six months through process adjustments and team restructuring.

Make Intentional Investment Decisions

Apart from quality issues, the data revealed another interesting topic. Of the 170 items delivered, only six were related to Governance, Risk & Compliance (GRC). Eight were focused on Technical Debt. Combined, these accounted for just 10% of overall cycle time. Industry data suggests that mature organisations typically invest 10% of their capacity in Risk and 15% in Technical Debt 1. Given the critical importance of system security, data security, privacy, delivery speed, and system scalability, a spend of just 10% on these topics seems like an approach that is potentially stockpiling future costs and significant problems.

Prioritising one category of work over everything else is acceptable when there’s clear business justification, but this can’t go on indefinitely. Over time, investments need to be balanced and they need to be intentional. In this organisation, this was not true. The defect, debt, and risk work wasn’t the result of specific, proactive decisions. Instead, defect work was mostly the result of a faulty process. The risk and debt work represented the engineering team’s desire to address issues they could no longer ignore. This work was done covertly and with a sense of frustration. “We’re not spending enough time taking care of essentials, and I’m really worried something bad is going to happen.” was the sentiment in the team. None of this work was being reported or discussed at the executive level.

The execution of quality, security, compliance, and technical debt strategies is the responsibility of engineering. However, how this work is prioritized and how it competes with feature development for attention is a business problem. Given finite capacity and excessive demands, there will always be too much work to do, and none of it can be done for free. How we choose to invest our time requires a proactive, intentional, and visible decision-making process that involves the business, not just engineering. Understanding where you’re spending your time today and making this highly visible is a great place to start.

Hiring into an Inefficient Process

One final insight from this organisation: The team has been growing rapidly, expanding from 45 to 60 people in nine months, with plans for further growth. However, adding more people to an inefficient process will only increase the scale of inefficiency. The goal of growing engineering teams is to deliver more, but if growing the team only increases complexity and inefficiency, tensions between engineering and the business will escalate faster than delivery output.

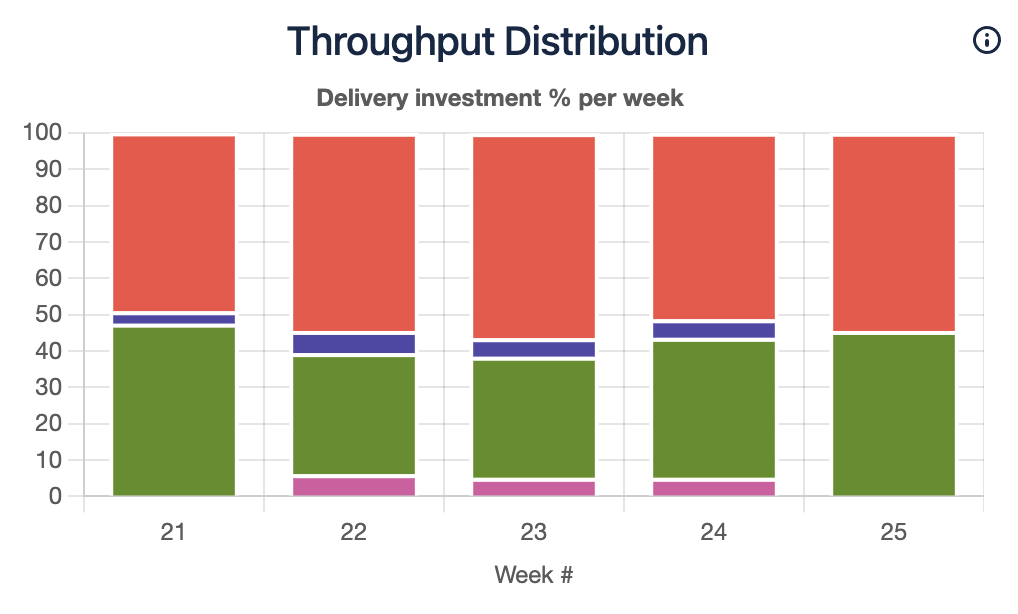

A better approach would be to identify and fix the quality issues within the team’s process first. Figure 2 illustrates the significant impact defects were having on weekly delivery investment in this organisation. The team’s plan to reduce the time spent on bug fixes from 40% to 30% is a good start, but the team shouldn’t stop there; 25% or even 20% is achievable. A reduction of 20% is the equivalent of saving one week of cycle time over a five-week period. For a team of 45, this is equivalent to adding nine people. Finding and removing inefficiencies is more effective than simply adding more people. Once the inefficiencies are addressed, the team would be in a better position to grow effectively.

Figure 2. Delivery investment % by week from Delivery Flow

Conclusions

This post reiterates previous arguments: Make all of your work visible to the business, quantify the demands on your team, and understand the finite capacity within your group. However, it also introduces the concept of delivery investment. Understanding the source of your work and the types of tasks your team handles is crucial. In most organisations, a lot of this work is hidden but often assumed to be the responsibility of engineering. Remember, demands will often exceed your team’s capacity, and every task has a cost in terms of people and time. How we balance our investment of time and effort is a critical business decision. Ensuring that both engineering and stakeholders understand delivery investment and take a proactive, balanced approach over time is vital to the health of our delivery systems and the products they produce.

1 Planview 2023 Project to Product State of the Industry Report